Thursday, April 23: Midnight at the East River Hotel

Just before midnight on a mild spring evening, Mary Miniter was playing cards in the back room of the East River Hotel when she heard the door bell ring. This was a common occurrence at the East River Hotel, a five story brick building at the corner of Water and Catherine Streets in a sordid lower Manhattan neighborhood noted for its similarity to London's Whitechapel slums. The hotel was located near some of New York's docks, and primarily existed to provide beer and beds for liaisons between sailors and local prostitutes. Mary, herself, was a prostitute, and was such a regular customer that the bartender, Edward Fitzgerald, asked her to open the door for him as he tended to thirsty customers. Mary let in an odd pair - an older, grey-haired woman who, by all accounts, had been unmercifully aged by years of plying her trade, and a much younger man (half his companion's age, Mary would later guess), who had a blonde mustache, a dented black hat, and a funny, German-sounding accent. The man politely requested a room for the both of them, bought the woman a ten cent pitcher of beer, and headed up the wooden stairs to Room 31 on the top floor.

Friday, April 24: The Body is Discovered

At around 9 o’clock in the morning, Eddie Fitzgerald walked along each floor of the East River Hotel, banging on every door to ensure the occupants from the past night had vacated their rooms to make space for Friday’s customers. When he got to the top floor, nearly all the rooms had already been emptied out and the doors left open. Only Room 31, at the end of the hallway, was still locked. Fitzgerald knocked once. No response. He rapped his knuckles against the door a second time. Still, nothing. Probably exasperated, he took the master key and unlocked the door. Then, he screamed.

Fitzgerald had opened the door of Room 31 to a grotesque vignette: Carrie Brown’s body lay on its side atop dirty, blood-soaked bedsheets. Her left hand was clutching her chest (several reporters later claimed it was as if she had been frozen in her final moments of agony) and her right hand was twisted underneath her body. Her back was to the door, so it was not until the police arrived on the scene about an hour later that they discovered her entire head had been wrapped tightly in an old white cotton skirt. When they took off the skirt, they saw two huge bruises on her neck that indicated Brown had been strangled. The source of the blood was a massive, gaping wound that ran up from her pelvis to the top of her abdomen. A knife, apparently the one used for the mutilation, had been almost casually discarded alongside the body.

The police flew into action. Immediately, they identified the three people who had witnessed Brown and her companion walk up the stairs the previous night—Fitzgerald, Mary Miniter, and the bartender Samuel Shine—and took them to the Oak Street Station for further questioning. Fitzgerald soon revealed that, a short while after Brown and her companion had gone upstairs, a man only known as "Frenchy" had also requested a room. He was given Room 33, diagonally across the hall from Room 31.

The police spent the rest of the day canvassing the neighborhood for "Frenchy" and anyone else who had occupied the East River Hotel the previous night. At around 10 o’clock in the evening, a local prostitute pointed out “Frenchy” to the police. A plain clothes police officer arrested the person identified, a tall, thin man with a swarthy complexion who, upon being handcuffed, immediately declared, "Me do nothing." When "Frenchy" was brought into the Oak Street Station for questioning, it was discovered that his shirt and stockings were stained with blood. At midnight, the police shooed out all reporters from the station house and escorted their new prisoner to the cell where they would keep him for the night.

Saturday, April 25: American Ripper

On Saturday morning, New York was ablaze with rumors. Almost all of the city’s major newspapers ran headlines declaring that Carrie Brown's murder was the work of Jack the Ripper. According to the papers, the infamous London butcher had certainly arrived in Manhattan after a three year hiatus from his bloody work on the other side of the Atlantic. The press pointed out the eerie similarities between the death of Carrie Brown and Jack the Ripper’s five victims: all of the murdered women were prostitutes, had been strangled and then brutally mutilated, and met their demise in the two cities’ poorest neighborhoods. Although some reporters commented that the incisions made by London’s Ripper were much more surgical and precise than the rough and jagged cuts found on Carrie Brown's body, many New Yorkers panicked, believing Jack the Ripper had come to terrorize Manhattan.

Meanwhile, the police searched frantically for Carrie Brown’s companion—the light haired, German-accented man wearing a dented black hat. Around 4 o’clock in the afternoon, Thomas Byrnes, the Chief Inspector of the Police Department, chewed on his cigar (as was his habit) and confidently told reporters that Carrie Brown’s companion was undoubtedly the murderer. Byrnes explained that they had arrested “Frenchy” because he was the supposed-murderer's acquaintance and might yield information about the wanted man’s whereabouts. The two were apparently notorious among local prostitutes for their deviant sexual desires and their preference for older, more ragged-looking women. Throughout the day, several men matching the supposed-murderer's description were arrested, but most were let go after being questioned by the police.

As Byrnes puffed his cigar and boasted to reporters that Carrie Brown's companion would soon be caught, a French-speaking detective interviewed “Frenchy.” The nervous prisoner explained in broken French that his name was Ameer Ben Ali, he lived in Brooklyn, and the bloodstains on his clothing were from the menstrual blood of Alice Sullivan, a prostitute whom he had slept with on Thursday morning.

Caught up in the terror that Jack the Ripper had arrived in New York City, very few people seemed to notice that the brass key to Room 31, which was unmistakably engraved with a large 3-1, was reported to be missing from the crime scene and had yet to be found.

Sunday, April 26: The Search Continues

On Sunday, the search for the light haired, German-accented man took on a heightened sense of urgency in Police Headquarters. Haunted by his own words, Inspector Byrnes grew increasingly anxious to catch Carrie Brown’s murderer. In 1888, as Jack the Ripper indulged in his bloody work, Scotland Yard famously failed to apprehend the serial killer. Their inability to catch London’s famous fiend became an international embarrassment and Scotland Yard, which in 1888 was regarded as the best police force in the world, was lambasted by both the press and other police departments. At the time, Byrnes had famously scoffed at Scotland Yard’s incompetency and declared, “I am certain that no such crime or series of crimes would go unpunished here.”

A magazine cover making fun of Scotland Yard's failure to catch Jack the Ripper

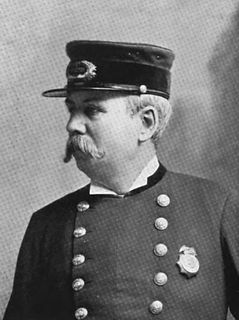

Inspector Byrnes

New York City had not forgotten those comments, and the Carrie Brown case provided the perfect opportunity for Inspector Byrnes to vindicate his earlier declaration. To Inspector Byrnes, the two parallel murders had become a grisly arena for an international policing competition. Byrnes seemed to think that, if he could catch his Ripper while Scotland Yard had failed to apprehend theirs, then it would anoint him as the best detective in the world.

Only, he, too, could not find his murderer.

Monday, April 27: Uncertainty Abounds

Monday brought unseasonable heat—temperatures reached the mid-eighties in the afternoon—and Inspector Byrnes was sweating. He began the day by adamantly denying he had ever declared the light haired, German-accented man to be the murderer. When a New York Herald reporter pushed back and noted that all of the city’s newspapers had printed some version of that statement, Byrnes angrily snapped at the reporter.

Later in the day, the same question was put to him, and this time Byrnes refused to give any conclusive answer. "The murderer may be ‘Frenchy,’ his cousin, or some other man," the usually supremely confident Inspector grumbled. "Now you know as much as I do about it."

In between the two conversations, Inspector Byrnes seemed to start his investigation completely over from scratch. He re-interviewed all of the witnesses, sent detectives to

Police Headquarters at 300 Mulberry Street

re-visit the East River Hotel (which, since the newspapers reported the murder on April 25, had become a popular destination for morbidly curious New Yorkers), and then had his men seal off Room 31 and Room 33.

Meanwhile, more information was coming to light about his current prisoner, Ameer Ben Ali. Ben Ali had been arrested twice in the past eighteen months: once for begging, and once for biting the arm of a prostitute so viciously he drew blood. When he was brought into the Oak Street Station for questioning on the night of April 24, Ben Ali said he worked at a hotel in Jamaica, Queens. However, when a French-speaking detective handcuffed himself to Ben Ali and traveled to Jamaica in search of Ben Ali’s workplace, the prisoner shrugged and admitted he had never worked in a hotel. In fact, such a hotel did not exist, he casually confessed.

The Elevated Train the detective and Ben Ali rode from Police Headquarters to Jamaica, Queens

As Inspector Byrnes grumbled and Ameer Ben Ali led detectives on a wild goose chase, New Yorkers learned the tragic story of Carrie Brown. She was born Catherine Montgomery in 1835 in England, and came to Salem, Massachusetts at the age of fifteen. There, she met and soon married a well-to-do sea captain named James Brown. Carrie quickly immersed herself in her new lifestyle. She became a member of the Central Baptist Church, dazzled Salem's social scene with her quick wit, and gave birth to two daughters and a son. However, soon after the births of her children, Carrie fell into a depression and began drinking heavily. Her entire demeanor changed, and her life with it. Her happy marriage to Captain Brown began to crumble, she began treating her children cruelly, and despite every effort made by her family and friends, she refused to give up drinking. A few years after the Civil War ended, Captain Brown contracted a fever and died off of the coast of Africa. Their marriage had grown so bitter, and his distrust of his wife so great, that Captain Brown only left Carrie a single dollar. The rest of his property he left to his uncle, to look after until the children came of age.

Depressed, drunk, and dejected, Carrie moved to New York City where she tried to work as a domestic servant. However, her drinking habits quickly got her fired and she turned to prostitution. Carrie became well known in the Fourth Ward neighborhood as "Old Shakespeare," a nickname she earned due to her proclivity for correcting her clients' grammar. Due to her age (she was fifty-six in 1891), she struggled to solicit clients and on April 23, she was completely broke. That afternoon, a fellow prostitute took pity on her and bought her a measly lunch of corned beef, cheese, and cabbage. After wolfing down her meal, Carrie Brown stumbled off into the early evening looking for someone—anyone—willing to pay for her services.

Tuesday, April 28: The Noose Tightens

A series of cool breezes seemed to calm the state of affairs at Police Headquarters on Tuesday. Inspector Byrnes had returned to his normal state—the uncharacteristic brief moment of fluster had passed, and his usual enigmatic and confident demeanor had returned in full force. While some detectives half-heartedly headed out from Police Headquarters to renew their pursuit of the light haired, German-accented man, the urgency that dominated the police department’s activities over the past few days had seemingly lost its grip. Captain Richard O’Connor, the officer in charge of identifying witnesses to Carrie Brown’s murder, exemplified this new attitude. He spent all day sitting in his office, occasionally mustering up the energy to peer out of his window at the reporters in the building across the street.

Unlike the past few days, in which nearly every hour conjured a new sighting or story of the wanted man, no such reports emerged on Tuesday. The people behind the most tantalizing leads were suddenly nowhere to be found. A stout brothel-owner named Mrs. Harrington and one of her prostitutes, a red-haired and freckled woman known as Dublin Mary, had told the police that the supposed-murderer was a regular customer of theirs, and that they could easily identify him. While the police had spoken of this lead several times over the past few days, no one at Police Headquarters mentioned either Mrs. Harrington or Dublin Mary on Tuesday, nor could reporters find the two women to comment on their familiarity with Carrie Brown’s companion.

A completely different story that had also garnered attention recently was that of a Swedish sailor who knew incredibly specific details of the gruesome murder not printed by the newspapers or spoken of on the streets. By Tuesday, it was as if that story had never been heard around Police Headquarters. And the most promising lead—a night clerk claimed a man had stumbled into the Glenmore Hotel (which was only a short walk from the East River Hotel) just after midnight on the night of the murder covered in blood—failed to register even a flick of interest from Inspector Byrnes and his men.

A typical policeman

of this era

The police were keeping nearly all the witnesses to the crime locked up in the Tombs, New York City’s primary house of detention for people awaiting trial. The Tombs were originally built in the middle of Manhattan’s most dangerous slum, the Five Points. For much of the first half of the nineteenth century, the Five Points was a bawdy, disease-ridden neighborhood where New York’s poorest citizens were crowded into shabby wooden tenements. Crime abounded and depravity flourished.

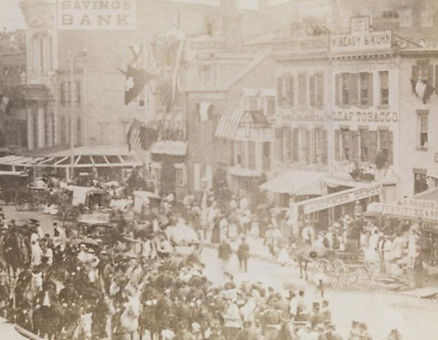

The Five Points a decade before the Tombs were built

In 1838, Tombs were erected in the center of the Five Points as a giant, permanent reminder (or wishful thinking) of the police’s power over crime in the city. The Tombs earned its ominous nickname not because of the gallows that it housed in its courtyard, but instead because the building’s eccentric architectural style was supposedly inspired by an ancient Egyptian mausoleum. By 1891, as Byrnes hunted Carrie Brown's murderer, the Five Points neighborhood was long gone (replaced by Chinatown and Manhattan’s Civic Center), but the Tombs remained.

The Tombs, in all its pseudo-Egyptian glory

The only witness not confined to the Tombs was Ameer Ben Ali, who was held in one of the cells beneath Police Headquarters at 300 Mulberry Street, a fifteen minute walk uptown of the Tombs. While reporters and the occasional visitor were allowed into the Tombs, a Police Department rule absolutely forbade anyone that was not either Inspector Byrnes or a smattering of his hand-picked officers into the cells at Police Headquarters. The only information that came out of those cells was information Byrnes wanted to share. As Tuesday evening fell, streets of New York began to buzz with rumors: did this mean Ben Ali was Byrnes' man?

Wednesday, April 29: Ben Ali Faces the "Third Degree"

It had been five days since Carrie Brown's body had been discovered, and the New York City Police Department had arrested over one hundred men who matched the description of her companion from the past Thursday night. But, by Wednesday evening, every single one of them had been released. The vast majority of these suspects were not even questioned by the police—more often than not, Inspector Byrnes would take one look, or read a short telegram description, and declare that the man was not Carrie Brown’s murderer.

Instead, the Police Department’s focus seemed to pivot away from hunting a light haired, German-accented man with a dented black hat, and instead toward searching for a man that more or less resembled the current prisoner, Ameer Ben Ali. In Jersey City, detectives arrested a Moroccan immigrant who said he was called “La Arabia” (which was almost certainly a nickname) solely because, according to one detective, the Moroccan “looked exceedingly like a man of blood.” After questioning the man, the detectives found out that “La Arabia” had previously lived in London, and, in a weird stroke of fate, had actually been arrested as a suspect in the hunt for Jack the Ripper. As soon as word of the arrest reached Police Headquarters, however, Byrnes sent over one of his subordinates with orders to release the man. He gave no explanation why "La Arabia" was to be let go.

Since Monday, Inspector Byrnes seemed to dismiss every new piece of information that was brought before him. Instead, his focus was almost solely

The Jersey City Ferry depot in Manhattan

on Ben Ali, who was shackled in a cell beneath Byrnes’ office. Newspapers hypothesized that Byrnes was going to apply his infamous “Third Degree” treatment to elicit a confession out of the terrified Ben Ali.

In the late nineteenth century, as is true today, the best way to ensure a conviction was by a confession. The “Third Degree” was Byrnes’ favorite tool to force confessions from the most hardened of criminals and it became a famous, if not instrumental aspect of the police under his reign. The process was essentially psychological and physical torture. Psychology was a relatively new science at the time, and Byrnes’ use of it for crime-fighting was celebrated around the world as a cutting-edge policing technique. Byrnes delighted in sharing how his “Third Degree” was able to wrench confessions out of the worst murderers, rapists, and thieves. It became so celebrated that a play, and later a movie (both called “The Third Degree”), featured its hypnotic powers.

Detectives preparing a suspect for his "Third Degree" treatment

as Byrnes watches on

It went like this: as soon as a promising suspect was arrested, Inspector Byrnes would have them brought into his office and seated. The poor suspect was never told why they had been arrested. Instead, Byrnes—puffing a cigar that peeked out from under his voluminous grey mustache—would make casual conversation with the man or woman seated before him. During their conversation, the Inspector would subtly encourage the suspect to talk about what they had been doing when the crime was committed. He got them to tell the story several times. If the suspect repeated the same details and wording every time, Byrnes took that to mean the man or woman had made up the story, memorized it, and was reciting their alibi automatically from memory. If Byrnes, through this test, determined a suspect was guilty, then the Inspector would continue making conversation without mentioning the crime. However, as their discussion went on, Byrnes would casually reveal evidence of the crime. The Inspector might use the murderer’s knife to open an envelope, or a handkerchief stained with the victim’s blood to wipe his brow. If the shock of seeing the evidence of their crime before them did not rattle a suspect into confessing, then two detectives would come in and take the suspect down to one of the cells beneath Police Headquarters.

Byrnes often held his suspects in those cells for days at a time without food to induce extreme psychological and physical pressure. After being subjected to this torture, Byrnes’ suspects often confessed to a crime they may or may not had committed. If that failed, Byrnes would roll up his sleeves, put out his cigar, and beat his suspects into confessing. By 1891, the Inspector had secured several high profile successful confessions from murderers and gang leaders through his famous “Third Degree” interrogations. He almost certainly believed that he could easily force a confession out of Ben Ali and, by doing so, earn the moniker of the detective who caught Jack the Ripper.

But he was mistaken.

Thursday, April 30: Bloodstains and Lies

Despite assuredly being tricked, pressured, starved, and beaten in the bowels of Police Headquarters, Ameer Ben Ali did not confess. Nonetheless, at half past four in the afternoon on Thursday, Inspector Byrnes’ right-hand man Inspector William McLaughlin hauled Ben Ali from 300 Mulberry Street to the Court of General Sessions. McLaughlin brought Ben Ali to the chambers of Judge Randolph Martine, who announced Ben Ali was formally charged with the murder of Carrie Brown.

Even though he had not confessed, Ben Ali was still arraigned on the basis of two things: a series of bloodstains that had been discovered in Rooms 31 and 33 of the East River Hotel, and his deviant nature.

When detectives visited the scene of the crime around noon on April 24, they noticed a pool of blood by the side of

A map of Lower Manhattan with the some of the case's important locations

the bed with some imprint, like a footprint, and the bloody marks of several fingerprints on the door. The detectives also swore that there were tiny—barely discernible, they said—spots of blood that formed a trail from Room 31 to Room 33, across the hall. They claimed that the door to Room 33 had blood marks on both sides, and the chair, bedding, and floor in that room were all also stained with blood. The District Attorney, DeLancey Nicoll, who had met McLaughlin and Ben Ali in Judge Martine’s chambers, explained to Martine that the bloodied stains had been cut out of Rooms 31 and Room 33 when the rooms were sealed on Monday, April 27. Nicoll then disclosed to the judge that the prosecution intended to prove the blood found in the East River Hotel was identical to the blood that the police had initially noticed on Ben Ali’s clothing, and the blood they later discovered that was under his fingernails.

The floor plan of the fifth story of the East River Hotel. On the night of April 23, Carrie Brown and her companion stayed in Room 31, while Ben Ali stayed alone in Room 33

This development surprised many of the reporters who had been covering the case since its beginning. A few of them—including the famous muckraker Jacob Riis—had been in Room 31 and Room 33 the day after the murder. Other than the bedding underneath the corpse, none of them remembered seeing any bloodstains in Room 31.

The second part of the murder charge against Ben Ali was his deviant nature. The prisoner was well-known among the prostitutes of the East River waterfront as a sexual pervert, who frequently bit and beat women. According to Nellie English, a prostitute who had once consorted with Ben Ali, it was his habit to take women to the East River Hotel, have sex with them, and then leave the room to prowl the hallways late at night. If Ben Ali heard a door close (signifying that a prostitute’s companion had left), he would go into that room and rob the woman as she was getting dressed.

Chambers Street (the Court of General Sessions is the darkly-colored building behind the horse-drawn fire brigade)

Carrie Brown was one of the few East River prostitutes who would still sleep with Ben Ali despite his vicious reputation, and he had been seen in her company several times in the days leading up to her murder.

Then, Nicoll discussed the matter of Ben Ali's lies. Ben Ali lied to the police several times: he claimed he had not slept in the East River Hotel on the night of April 23 (he had), he said he worked at a hotel in Jamaica (he later admitted he was a fruit-seller in Brooklyn), and swore he did not know the prostitutes who had come forward to identify him (to a woman, they all said they knew him, and many had slept with him at some point in time or another).

Throughout this meeting, Ben Ali kept professing his innocence to Judge Martine through a translator. A former prosecutor himself, Judge Martine listened to Ben Ali’s desperate pleas with little sympathy and assigned him counsel from the firm of Levy, House, and Friend. After the meeting had concluded, Inspector McLaughlin took Ben Ali by the arm and led him back to Police Headquarters, where he was returned to his cell underneath the building.

Friday, May 1: Ben Ali Shares His Life Story

Friday was a dull, grey day. It was a little cold for mid-spring and occasional bursts of rain chilled New Yorkers who were unlucky enough to be caught outside when the skies decided to open up.

In the morning, two of Inspector Byrnes’s detectives traveled to the Queens County Jail. The sheriff of Queens County had written to Byrnes and informed the Inspector that he had a couple of prisoners who had information about Ameer Ben Ali.

Earlier that year, Ben Ali was arrested for vagrancy (he was caught begging and faking a broken arm) and had been sent to the Queens County Jail. The two prisoners, David Gilloway and Edward Smith, had been locked up with Ben Ali for several months. Gilloway and Smith claimed that, when he was thrown in jail, Ben Ali had smuggled in a knife which matched the description of the weapon found next to Carrie Brown’s body. On top of that, the two men swore that Ben Ali had a vicious personality and once even tried to stab another prisoner with the knife.

At 5 o’clock in the evening, Ben Ali was transported from Police Headquarters to the Tombs. He was confined to Cell No. 63, where he was to remain until his trial. An hour after he was put into the cell, the lawyer Emanuel Friend (of Levy, House, and Friend) arrived at the Tombs along with an interpreter to meet with Ben Ali. However, instead of discussing the details of the case, Ben Ali told Friend his life story.

The murderer's knife (top) compared to the knife Ben Ali had in the Queens County Jail (below)

Ameer Ben Ali was a tall, thin middle-aged man. By all accounts, he had exceptionally long limbs, and his arms and legs often stuck out an extra six inches or so beyond

the hems of his clothing. His right arm was decorated with several tattoos. A Christian cross was featured above an Islamic crescent on one side of his forearm. On the other, he had two portraits: one of himself in military regalia and one of a woman, ostensibly his wife.

Through the interpreter, Ben Ali told Friend that he was born in a mountainous village in northern Algeria and was a member of a Berber tribe. He explained it was not his tribe’s practice to acknowledge dates and, as such, had no idea of his exact age or in what years the major events of his life had occurred.

Around 1870, Ben Ali said he joined a French provincial regiment and fought on behalf of his colonial overlords during the Franco-Prussian War. He was wounded twice during the war – once in the shoulder and once in the leg. He stayed in the French Army for nearly a decade after, and then joined the crew of a fruit ship that traveled between Africa and South America. After several years of transatlantic voyages, Ben Ali decided to leave his wife in Algeria to move to Brazil and try his luck. However, he struggled to make ends meet. A few years later, in either 1888 or 1889, Ben Ali immigrated to Brooklyn where he took a job as a fruit seller.

Two sketches of Ben Ali

He had been selling bananas—despite the occasional jail sentence—ever since.

When he had finished telling Emanuel Friend his life story, Ben Ali looked the lawyer in the eyes and once again proclaimed his innocence. This display thoroughly convinced Friend, who left the Tombs that night determined to see his client go free.

Saturday, May 2: Inspector Byrnes' Revolution

Ameer Ben Ali was probably unaware that he was caught in the middle of a revolution. Since 1880, Inspector Thomas Byrnes had been transforming the New York City Police Department from a glorified drinking club into the international standard of a modern police force.

Byrnes was born in Ireland in 1842, and, as a young boy, moved with his family across the Atlantic to a New York City tenement—those dilapidated wooden structures that housed Manhattan’s poorest and most down-trodden inhabitants. As a teenager, he joined a local volunteer fire company. When he was nineteen years old, he enlisted in Colonel Elmer Ellsworth’s “Fire Zouaves” regiment to fight in the Civil War. Byrnes’ service did not last long and he left the war behind as soon as he was able. After the war, the Inspector would chuckle and admit his greatest military accomplishment was running from the battlefield just as fast as anybody else.

When Byrnes’ enlistment was up in 1863, he returned to New York City and became a patrolman at the Mercer Street Station. He was steadily promoted over the next fifteen years, and, in 1878, he gained city-wide fame when he caught the burglars of the Manhattan’s Savings Bank who had made off with millions of dollars. That bust earned him the job of Inspector and he was placed in charge of the city’s Detective Bureau in 1880.

The flamboyant uniforms of the "Fire Zouaves"

Over the next eleven years, Byrnes completely transformed the Police Department. He centralized its bureaucracy and placed himself at its beating heart. He incorporated the relatively new science of photography and popularized the idea of the mugshot (Byrnes had a “Rogues’ Gallery” in Police Headquarters that featured the portraits of over five hundred of the city’s most notorious criminals). And he created policing networks that spanned both the country and the Atlantic Ocean. In 1891, Byrnes was in near-constant communication with most major American police forces and several European departments as well.

But Inspector Byrnes’ greatest achievement was earning the trust of New York City’s elite. Before his appointment as head of the Detective Bureau, the wealthiest New Yorkers often favored the services of private detective agencies over the police force. There was even a widely-held belief among Wall Street financiers that the police were more likely to steal their money than they were to protect it.

The "Rogues' Gallery" in Police Headquarters

In order to earn the trust of these citizens, Byrnes turned the police into the ultimate protectors of elite interest. He established a satellite

office in Wall Street with telephones connected to every bank (the first use of telephones in the Police Department), so that he was quite literally only a phone call away for bankers. Byrnes also instructed his detectives to ditch their usual uniforms, and, in an effort to directly appeal to elites, dress like gentlemen by donning natty suits and hats. Byrnes, himself, was known to ditch his Irish brogue for an upscale English accent when talking to a financier or industrialist.

Byrnes posing in the lobby of Police Headquarters

The Inspector also acted as a personal fixer for New York’s rich. He would often exchange favors (breaking a strike, quieting a rowdy son-in-law, covering up a scandal) for stock tips. Through this, he became close friends with Jay Gould and Cornelius Vanderbilt Jr., among others. When Byrnes retired in 1895, his net worth was over ten million dollars (in present value) and his most prized possession was an invitation to a dinner held in his honor by the New York Stock Exchange.

Although he was almost fifty in 1891, Inspector Byrnes still possessed the muscular physique of a younger man, and always carried himself so that he was never an inch shorter than his full height of 5’11”. He had spent the past eleven years building the police force in his formidable image, and he was not about to let a murder of a prostitute dent his sterling reputation.

Sunday, May 3: The Baltimore Trunk Tragedy

On Sunday, a May cold spell seemed to momentarily pause the investigation into the murder of Carrie Brown. Ameer Ben Ali spent the entire day in his cell, alternatively dozing on his cot or staring wistfully out into the hallway. Inspector Byrnes had escaped the city and quietly retreated to his weekend home, a riverside estate in Red Bank, New Jersey. Despite the lack of new developments, New Yorkers simmered with excitement. The city had not seen such a high profile murder case since 1887, when Byrnes solved the mystery of the Baltimore trunk tragedy.

On January 22, 1887, a tin-covered trunk arrived in Baltimore. No one came to collect it and it sat untouched for four days. On the fifth day, the unmistakable stench of rotting flesh began to emit so strongly from the package that the police were called. The trunk was brought to a local station house and forced open. Inside, lay the torso of a young man. His legs and left arm had been cut off and neatly packed alongside the rest of his body. He had been decapitated, but his head was not included among the grotesque contents of the trunk.

Since the trunk had come from New York City, Byrnes was notified and he sent down several detectives to identify the body. The corpse was quickly discovered to be that of August Bohle, a German butcher from Brooklyn. Almost immediately, Byrnes focused his attention on Bohle's roommate, a former saloonkeeper named Edward Unger. Two detectives were sent to arrest the man and were under strict instructions to not inform him why he was being apprehended. Without saying a word, the two detectives picked up Unger, handcuffed him, and silently brought him to Inspector Byrnes’ office.

Byrnes' house in Red Bank, where he

spent his Sunday

The Inspector, a cigar casually held in his mouth, stared at Unger in silence for several minutes. Then, Byrnes abruptly ordered his detectives to take Unger to the cells below and lock him up with little food. The former saloonkeeper spent the entire night underneath Police Headquarters.

The next day, Unger was brought into Byrnes’ office again. Spread out on the Inspector’s desk lay the instruments of the crime: the bloody hammer that had been used to strike the fatal blow, the rubber cloth on which Bohle’s body had been placed, and the knife and saw that had been used to dismember the German butcher. Byrnes did not acknowledge their presence, but instead initiated a strange parade.

In walked Bohle’s and Unger’s landlady, who pointed at Unger, identified him as Bohle’s roommate, turned around, and walked out of the office. Unger tried to talk to her as she left, but was quickly silenced by a detective. As soon as the landlady had gone, the detectives brought Unger back to his cell. A half hour later, the same process occurred again, but this time it was a different acquaintance who came in, pointed at Unger, identified him as Bohle’s roommate, turned around, and walked out. This process was repeated at thirty minute intervals for the next several hours with different people who knew both Bohle and Unger coming in one after the other. By the end of the day, Unger—who had kept his composure since he entered Police Headquarters—began to crack.

Unger was then left alone in his cell for the next thirty-six hours. Late in the evening of the next day, after he had fallen asleep, Unger was roughly shaken awake and pushed into a dimly lit hallway. As Unger stepped out of his cell, he tripped. When he looked down to see what had caused him to stumble, he realized he had caught his foot on the tin-covered trunk that had held Bohle’s mutilated body. Unger recoiled, but managed to compose himself and took a few steps down the hallway. That's when Byrnes emerged from the shadows. The Inspector held up half of Bohle’s coat and calmly asked Unger if he knew where the other half of his murdered roommate’s coat was. This rattled Unger so deeply that a detective put a sympathetic arm on his shoulder and told him it was okay to sit down. Unger gratefully collapsed on a sofa. But when he looked down, he nearly fainted. He was sitting on the same blood-stained sofa on which August Bohle had been murdered.

Sketch of Edward Unger

Unger was so traumatized he had to be carried back to his cell. The next morning, he confessed to murdering Bohle, cutting up his body, and packing it in a tin-covered trunk that he sent down to Baltimore. Within a month, Unger was convicted of manslaughter in the first degree (at the last moment, his lawyers successfully convinced the jury the killing was partially in self-defense) and sentenced to twenty years in Sing Sing prison.

New Yorkers had not forgotten the spectacular fashion in which Byrnes had applied his famous "Third Degree" treatment to solve the Baltimore trunk tragedy and they were expecting a similar level of theatrics for the Carrie Brown case. For every day that Byrnes failed to get a confession out of Ben Ali, New Yorkers grew less and less certain that the Algerian was the guilty man.

Murderer's Row in the Tombs, where Ben Ali

spent his Sunday

Monday, May 4: Mr. House Fires the First Volley

After a quiet couple of days, Frederick House started the week with a lot of noise. House (of Levy, Friend, and House) was the lead defense attorney for Ameer Ben Ali. Like his partner, Emanuel Friend, House passionately believed his client was innocent. When he spoke to a reporter about the case on Monday afternoon, he bridled with righteous anger from behind his steel-rimmed spectacles.

House sharply pointed out three glaring holes in Byrnes’ case. The first hole was the obvious difference in appearance between Carrie Brown’s companion and Ameer Ben Ali. The two men didn’t look alike in the slightest—the companion was light complexioned and probably of central European descent while Ben Ali was dark-skinned and of North African descent. Moreover, the first man was reported to be short, around five and a half feet or so, and Ben Ali was at least six feet tall.

A sketch of Carrie Brown's companion (left) compared to one of Ben Ali (right)

House then moved on to the second weakness: “Why, too, if Mr. Byrnes knew our client was the murderer, did he scour the city and country for weeks after other persons…?” To House, it made no sense that Byrnes arrested Ben Ali yet declared Carrie Brown’s companion to be the murderer, then conducted a massive and unfruitful manhunt for that man, only to turn around and accuse Ben Ali of the crime.

Mr. House saved his strongest point for last. “Why was it, again,” he asked rhetorically, “that intelligent reporters did not see those bloody tracks leading across the hall from room No. 31 to room No. 33, or, at least, the marks of their erasure had they been obliterated before? And how was it,” he continued, “that they failed to notice that No. 33 had the appearance of a slaughterhouse as Byrnes now says it had?” House was, of course, responding to Byrnes' claim that a trail of blood linked Room 31, where Carrie Brown and her companion spent the night, to a blood-soaked Room 33, where Ben Ali slept. While Byrnes swore this was definitive proof of Ben Ali's guilt, several reporters who had immediately followed the police to the crime scene had no recollection of seeing a blood trail between the rooms nor any blood in Room 33.

House finished his mini lecture by questioning why a trial date had still not been set. If Byrnes had the evidence of Ben Ali’s guilt like he claimed he did, House asked, then why not go ahead with the trial?

Byrnes had his reasons. He was most likely using this interim to smooth out his relationship with the District Attorney's Office. The history between Byrnes and the D.A.’s Office had not always been amicable. In fact, at times, it had been downright hostile.

In 1884, the New York City District Attorney Peter Olney had hired the Pinkerton Detective Agency (a private detective firm) to arrest Fredericka Mandelbaum, Manhattan's premier buyer and seller of stolen goods. Mandelbaum stood well over six feet and purportedly weighed close to three hundred pounds, yet she had managed to avoid the grasp of the police for nearly a decade. She operated with complete impunity out of a dry goods store on the corner of Clinton and Rivington streets. Mandelbaum's unique ability to simultaneously openly operate—if not flaunt—her criminal empire while staying out of the grasp of the authorities earned her the nickname, “Fredericka the Great.”

Fredericka Mandelbaum

Olney was fed up with the Police Department’s inability or unwillingness to take down Mandelbaum, so he secretly hired the Pinkertons. The Pinkertons enlisted a “stool pigeon,” a low-class criminal informant, to sell Mandelbaum a stolen piece of black silk. A few days later, an undercover Pinkerton agent bought the same piece silk off of the criminal empress and then arrested her for selling a stolen good.

One of Mandelbaum's extravagant dinner parties, whose invitations were so coveted that some police officers even attended. "Fredericka the Great" is seated at the far right.

The Police Department was completely shocked by Mandelbaum’s capture. Inside Police Headquarters, Inspector Byrnes was infuriated. He viewed Olney’s secret employment of the Pinkertons as both a betrayal and a declaration of war.

Olney had not stumbled into this operation naively; he knew he was provoking Byrnes. When asked why he had opted to hire private detectives instead of use the police, the District Attorney shrugged and said, “The police should be taught a lesson.”

During Mandelbaum’s trial, her lawyers (who, coincidentally, were the same firm that represented Edward Unger) claimed that Mandelbaum was merely a pawn in a massive power struggle between the District Attorney’s Office and the Police Department for control of New York City. The ruse worked. Attention shifted to the tension between the prosecutors and the police. As Olney and Byrnes glowered at each other, Fredericka Mandelbaum quietly slipped out of New York City and fled to Canada, where she lived peacefully and without interference from the law for the rest of her life.

A cartoon of Mandelbaum escaping as Olney (left) and Byrnes (right) argue

The Mandelbaum catastrophe was almost certainly very much still on Byrnes’ mind as he prepared for the trial of Ben Ali. He needed his relationship with the new District Attorney, De Lancey Nicoll, to work flawlessly for this trial. Inspector Byrnes had put too much on the line with this case. He could not afford another disaster.

Tuesday, May 5: Mr. Carnegie's Music Hall

On Tuesday evening, as Ameer Ben Ali sat on his cot in the Tombs, Andrew Carnegie’s newest project—a music hall on 57th street and Seventh Avenue—opened its doors for the first time. Despite the unusually chilly temperatures, five thousand people braved the weather to attend the Music Hall’s opening night. Carriages lined up well over a quarter mile down 57th street and, one-by-one dropped off well-dressed New Yorkers at the building’s glowing entrance. Although seats had sold out a week earlier, plenty of Manhattanites still bought standing room tickets at the door. Over two thousand people jostled shoulders with one another to find just enough space to crane their necks and catch a glimpse of the stage at the center of Mr. Carnegie’s Music Hall.

They were not disappointed. The hall was brilliantly illuminated by

Carnegie Hall in 1891, the year it opened

four thousand electric lights, a nearly unheard of luxury in the Gilded Age. Indeed, the interior was so brightly lit that some audience members later claimed to suffer from temporary blindness. The night began when four hundred singers clad in black and white took the stage and belted out a few ceremonial hymns. Then, the Episcopalian Bishop Henry Potter gave a blessing which was apparently so long and boring that Mrs. Carnegie began to noticeably fidget in her box above the main door. The audience, therefore, experienced a collective wave of relief when the bishop finished with a droning "Amen," and the music could begin. Out from the wings stepped the guest of honor, a tall, grey-haired man who gave a few awkward, jerking bows to acknowledge the thunderous applause that greeted him. As soon as Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky grasped the baton, however, his entire demeanor changed. It was the Russian composer’s first performance in the United States, and he dazzled as the New York Symphony Orchestra performed his “Marche Solennelle,” a triumphant and festive tune that was perfectly appropriate as the musical crown jewel in the Music Hall’s inauguration ceremony.

Andrew Carnegie’s Music Hall (it would not be known by its modern name, Carnegie Hall, for some time), was not just an extraordinary gesture of individual charity. It was an attempt to end one of the many wars for authority that fiercely raged across the island of Manhattan in the late nineteenth century. The particular conflict into which Carnegie was wading was over who controlled New York’s social scene. In the 1880s, the descendants of the old mercantile families that had been in the city for generations—names like Astor, Roosevelt, and Schuyler—had their position atop the social hierarchy threatened by the scores of rich financiers and industrialists who had made their wealth in the past decade or so. The old mercantile families responded by making traditional New York social institutions even more exclusive so that Vanderbilts, Rockefellers, and Goulds could not buy their way in.

The old guard's Academy of Music which held eighteen boxes (left) compared to the new guard's

Metropolitan Opera House (right), which held seventy

One of the most prominent symbol of the old guard’s grip on society was the Academy of Music opera house on 14th street. There were only eighteen boxes, and they were all owned by mercantile families who were so intent on making these boxes into a symbol of their social authority that they turned down William Vanderbilt (son of the famous Cornelius “Commodore” Vanderbilt) when he offered $30,000 (nearly $775,000 in present value) for a single box. Spurned, Vanderbilt gathered other members of the nouveau riche and, along with William Rockefeller, Jay Gould, and J.P. Morgan, financed a new venue, the Metropolitan Opera House. The Metropolitan Opera House was a wild success and within a few years, forced the Academy of Music to crumble. However, who controlled New York's orchestra scene was still up for debate in 1891, and the Music Hall on 57th street was Andrew Carnegie’s best attempt—as a member of the newly-monied class—to answer the question of social control in New York City once and for all.

As the ancient knickerbocker families and the nouveau riche flung their millions at each other and into the city, members of the middle class were at war with themselves. In 1891, the New York City middle class was predominantly comprised of Irish and German (both foreign-born and first-generation) Manhattanites. The middle class was divided into three political camps: socialists, independent (or Swallowtail) Democrats, and Tammany Hall. While all of these groups formed uneasy and short-lived alliances with one another at some point, they were trying to achieve fundamentally different versions of New York City. The socialists wanted a city ruled by its working classes; the independent Democrats sought to put educated, reform-minded individuals in charge of Manhattan’s municipal apparatus; and Tammany Hall was a notorious political machine that did everything it could to control City Hall and use that power to line its pockets with ill-gotten gains. The Republican party of this era was primarily a

Andrew Carnegie

Protestant, upper class endeavor that detested all three of the middle class political divisions. The chaotic political battles in Gilded Age New York City were so multi-faceted and confusing that they made its social warfare seem simple by comparison.

Not long after Mr. Carnegie opened his Music Hall, each and every one of these warring factions would find themselves drawn to a new battleground: a courtroom on Chambers street, where an Algerian immigrant named Ameer Ben Ali was to be tried for the crime of brutally murdering Carrie Brown.

Wednesday, May 6: Ben Ali in the Bowery

On Wednesday, cries of "Jack the Riiiiiiiiipper" probably pierced through the regular din of the Bowery, Gilded Age New York’s most vibrant and notorious thoroughfare. Dime museum managers, the professional descendants of P.T. Barnum (who had just died on April 7), did their best to attract crowds under the shadow of the Third Avenue "El" train as they promised to faithfully show exactly how Ameer Ben Ali brutally murdered Carrie Brown.

The Bowery originally gained prominence as the main path in and out of the Five Points, which lay just west of the street's southern end. As a two way road to New York’s center of depravity, the Bowery quickly developed a seedy reputation of its own. By 1891, it had become Manhattan’s

Painting of the Bowery at night

entertainment hub. Saloons, theaters, and dime museums spilled out from underneath the elevated train tracks and delighted those seeking a strong dose of hedonism.

Throngs outside some of the Bowery's houses of entertainment

The Bowery offered a full menu of experiences for locals and tourists alike. Most establishments along this artery usually offered at least one variety show a night. During these, the audience was regaled by mind-blowing gymnastics, bawdy song-and-dance routines, racist minstrel shows performed in blackface, circus acts like sword eating and fire breathing, comedic skits that satirized life in New York by mimicking an Irish brogue or a Fifth Avenue strut, boxing matches, and displays of human curiosities like supposedly ancient humans and "bearded ladies." Should these acts fail to fully enthrall their audiences, many of the Bowery’s establishments housed easily-accessible brothels in their backrooms.

When Gilded Age New Yorkers hankered for something a little more upscale, they went uptown to Madison Square Garden, where, depending on the night, you could attend an

Annie Jones, perhaps the most famous "bearded lady" of the late nineteenth century; note the photo was taken at 888 Bowery, NYC

extravagant performance of "Hamlet" or enjoy a three ring circus. If you found yourself humming a tune, you could go to Tin Pan Alley, the area surrounding Union Square, to buy the sheet music for one of the era’s wildly popular mass-produced, melodramatic, and formulaic songs. If you were in need of something a little more original, a song could be written for you in a matter of minutes. For New Yorkers who wanted to escape Manhattan, there was Coney Island to the east, one of the earliest American amusement parks offering beaches, boardwalks, roller-coasters, and relaxed behavioral standards.

Should a trip to the Bowery, Madison Square Garden, Tin Pan Alley, or Coney Island fail to satisfy New Yorkers’ need for the spectacular, they often turned to detective novels, one of the era’s literary innovations. In these, you could read about the adventures of Sherlock Holmes or, if you were looking for something a little more local, the dramatized exploits of Inspector Byrnes, who cowrote a series of his own semi-autobiographical tales with the help of Julian Hawthorne, son of The Scarlet Letter author Nathaniel Hawthorne.

Like nearly everything that touched the island of Manhattan, Ameer Ben Ali and the murder of Carrie Brown were quickly commercialized and spectacularized.

The cries of "Jack the Riiiiiiiiipper" were not to alert the police to another bloody murder, but rather advertisements for sidewalk exhibits put on by Bowery dime museums with larger-than-life images purporting to show how New York’s own Jack the Ripper had viciously murdered “Old Shakespeare.”

When Frederick House, Ben Ali’s lawyer, tried to have these exhibits shut down, several dime museum managers countered by offering to pay Ben Ali handsomely if he came to work for them as a human curiosity. Their job offers came with only one condition: they would pay Ben Ali a small fortune every week... Should he be acquitted.

Thursday, May 7: Tribute for Tammany

The seediness of the Bowery flourished thanks to an elaborate network of corruption called the Tribute System. The Tribute System was fairly simple. A police officer—casually referred to as a bag man—would dress in plain clothes and walk into an illegal establishment, like a gambling den, a brothel, or a saloon opened on a Sunday (it was illegal for most places to sell alcohol on Sundays). The cop would then join a game of poker, ask for a prostitute, or order a beer. Once his request was completed, the officer flashed his badge and politely suggest the owner pay a monthly payment for "P.P." (police protection) if the establishment wanted to stay in business. If the owner protested, the officer ditched the niceties, pointed his revolver at the owner’s head, and demanded the money for "P.P."

Sketch of the interior of Barney Flynn's Bowery saloon (based on the name, it most likely enjoyed Tammany protection)

Every month, the bag man would collect payments and deliver them to his boss, the precinct captain. The captain kept some for himself, gave the bag man a slightly smaller share, and sent the rest up to his superiors at Police Headquarters. Even the Police Commissioners (the four civilians appointed by the mayor to oversee the department) received a cut. This was a lucrative business; the Tribute System brought in $400,000 ($11,000,000 in present value) every year to be divvied up by police officials.

For the owners of these establishments, the monthly payments for "P.P." were usually a small price to pay to keep their illegal gambling dens, brothels, and saloons open and bustling without the possibility of police interference.

The Tribute System was also political. The businessmen and police officers involved in the city-wide corruption network were mostly Irish-American Tammany Hall members. This meant that illegal Tammany

businesses paid Tammany police officers for the privilege of being able to operate with impunity, while the police shut down their non-Tammany competitors.

Remarkably, Inspector Byrnes seemingly never partook in the Tribute System. While nearly every other police officer in the city could be bribed, Byrnes resisted temptation. One criminal was so frustrated by Byrnes that he even publicly complained to a newspaper: "I don’t know what kind of man Byrnes must be; we can’t touch him with money."

Now, Byrnes probably had no need to sully his good name by involving himself in the Tribute System. He didn’t need the money. He was, after all, receiving absurdly valuable stock tips from his wealthy financier friends named Gould and Vanderbilt. When he retired from the force in 1895, having only been a police officer for his entire life, Byrnes was worth nearly $350,000 (or, $10,500,000 in present value).

While Byrnes didn't really care about the Tribute System, he absolutely hated Tammany's political influence over the Police Department. Not only were most of the rank-and-file affiliated with the hall, two of the Police Commissioners (who were, technically, his bosses) were also Tammany members. These two—Charles F. MacLean and James J. Martin—kept promoting Tammany police officers, so that most of the high-ranking officers were loyal to MacLean and Martin instead of Byrnes. This infuriated Byrnes. The cigar-chomping Inspector had tried to sever these political connections a few times over the past several years, but Tammany was simply embedded too deeply. Disgusted by

Tammany Hall's Headquarters on 14th Street

its influence, Bynes publicly and frequently referred to Tammany Hall as "an evil of large dimensions."

His hatred for Tammany did not go unnoticed by the notorious political machine. By 1891, Tammany Hall had trained its sights on taking Byrnes down.

Friday, May 8: Jacob Riis Walks to Work

On a clear and cold Friday morning, Jacob Riis left his gabled, two-story house in Richmond Hill, Queens and began his daily commute to his office at 303 Mulberry Street. Riis was probably not walking with his usual vigor. He was the police reporter for The Sun and had been covering the Carrie Brown case since its inception, but nothing of note had happened for a few days.

A lack of development was no reason to show up late to work, however, and Riis continued on his trek to 303 Mulberry Street, the building directly across from Police Headquarters that served as the hub for the New York's police reporters.

Riis fancied himself the “boss” reporter of 303 Mulberry Street, and with good reason. He had been a journalist pretty much since he arrived in New York City from Denmark, and had been covering police news for the past fourteen years. Riis was known for his ability to consistently ferret out stories that both amazed and terrified New Yorkers. While other reporters patiently waited for official statements from the police, as soon as Riis heard of a crime he practically sprinted to the crime scene. One time he even tried to sneak along in a police

Jacob Riis

carriage, but, to his disappointment, was discovered and deposited on the street as the carriage rumbled on.

During his daily commute to 303 Mulberry Street, Riis walked through “The Bend,” the most notoriously squalid tenement neighborhood in New York City. Tenements were flimsy wooden structures with barely any light or ventilation. Greedy landlords packed recently arrived immigrants who were desperate for housing into tiny, prison-like apartments inside. In 1891, “The Bend” was home to the worst of the worst.

The Bend (left) and a tenement yard (right); both photographs were taken by Riis

As Riis walked through "The Bend," six-story creaky tenements rose above him on either side of the dirty cobblestoned street. When he looked left or right, he saw mazes of unpaved narrow alleyways spilling out between these buildings. Crisscrossing wires covered in the day’s laundry blocked out much of the sunlight, and cast large swaths of the area into a constant state of artificial darkness. Since the living conditions inside tenements were so miserable, “The Bend’s” inhabitants spent much of their time in the streets and alleys. Riis walked past peddler carts that formed improvised shopping aisles, wooden boards which were propped up on barrels to make counters, and sidewalks that were home to shady banks and employment offices wedged between grocers and tobacco bureaus. There was a constant buzz of noise; a careful listener could occasionally make out strains of Yiddish, German, and Italian which floated just below a thick, oppressive layer of that particular stench which comes from too many people crowded into too small of a space.

Riis was a muckraker: he was both fascinated and horrified by New York City’s tenements, and his daily walks through "The Bend" inspired him to expose well-to-do New Yorkers to the horrors of tenements. He hoped that his work might inspire reform-minded elites to focus their efforts on the poverty rampaging in these neighborhoods. However, mere words could simply not capture the squalor and hopelessness he saw everyday, so Riis taught himself photography. After a few mishaps (he set his house on fire twice and self-immolated once), Riis mastered the camera and in 1890 published his first, and most famous, book: How the Other Half Lives, which brought the grim realities of tenement living into the parlors of wealthy New Yorkers and is now widely considered to be the founding text of photojournalism.

Riis had dedicated his career to identifying and exposing the injustices of the world. He had met Inspector Byrnes many times and deeply respected him as a well-intentioned crime-fighter. But, as Riis walked to work on that cold May

morning, he was almost certainly playing back the events of the past two weeks in his head. He had been one of the first reporters at the East River Hotel on April 24. He saw no trail of blood across the hallway and no evidence of blood in Room 33. Yet, he trusted Byrnes. Even though Riis had made his mark as a fierce critic of Gilded Age New York, the Danish reporter believed the Inspector was a good man who did his job to the best of his ability.

But where was the blood?

All of this and more was probably banging around inside Riis’ head as he pushed

Riis (back corner) in his office at 303 Mulberry Street

open the door to 303 Mulberry Street, stepping inside toward another grueling day covering the New York City Police Department.

Saturday, May 9: Friends in Brooklyn

For days, Ben Ali had been asking the police to locate his friends in Brooklyn. Ben Ali tried to give directions to his apartment, but all he could manage to describe was that he used to live near a police station on the Brooklyn side of the ferry to Battery Park.

"Go there and find my friends," Ben Ali pleaded. "One was born in Tunis. People call them Turks, but they were my friends and they speak my language. Besides they have known me for a long time, and they know that I work and would not kill anybody. One of the men is named Jenalli and the other is named Bozieb. Jenalli lives where I stay and he knows where Bozieb is. Please bring Jenalli to me."

The ferry depot in Battery Park, to which Ben Ali was referring

The detectives who heard this plea just smiled. Ben Ali’s cry for help was said in startlingly good English for a man who had claimed he could speak none for the past three weeks. To the police, this just further proved the Algerian immigrant was a liar and a fraud.

To the lawyers of Levy, Friend, and House, these men—Jenalli and Bozieb—were potentially helpful witnesses who could testify to Ben Ali’s good character and provide counter-evidence to the prostitutes' claims of Ben Ali's violent

tendencies and sexual perversions. But, after a couple of days of searching all over Brooklyn, they could not find Ben Ali’s friends.

The challenge of finding these two men then fell to an unlikely candidate: the police reporter for the New York Herald. Unfortunately, his or her name has been lost to history. Newspapers rarely included bylines in the late-nineteenth-century, so unless a reporter gained extraordinary fame the way Jacob Riis had with How the Other Half Lives, they remained fairly anonymous to the New York public.

Frustrated by the lawyers’ inability to find Ben Ali’s friends—and perhaps inspired by Riis’ famous investigative journalism exploits—the reporter set off to locate Jenalli and Bozieb on a rainy Saturday. After a few hours of asking locals about a fruit stand run by Turks (the reporter remembered Ben Ali had admitted he worked as a fruit-seller), the enterprising journalist finally found a fruit stand off of Columbia Street. A man standing nearby gruffly mentioned that the two Turks who ran it lived on the second-floor of a tenement across the way.

Columbia Street; note the unfinished Brooklyn Bridge in the background

After climbing a set of creaky wooden stairs, the reporter knocked on the door of the street-side second floor

apartment. A tiny, elderly man of North African or Middle Eastern descent answered the door. He introduced himself as Jenalli. Here was Ben Ali's long undiscovered friend and roommate. When the reporter explained that they had come to inquire about Ben Ali, Jenalli invited them into his apartment, explaining "Ameer Ben Ali me know... He my friend." Inside the apartment were two more people, a red-haired woman who was Jenalli’s wife, and Bozieb, Ben Ali's other friend who spoke very little English.

With Jenalli’s wife acting as a translator, the reporter explained what had happened to their friend. The trio was shocked. They hadn’t seen Ben Ali for three weeks and had no idea what had befallen their missing roommate.

Soon, anger and disbelief replaced shock. "He was generous and very kind to children and would give them all his pennies,' explained Jenalli’s wife. "He was never known to insult a woman. If a man insulted him or hit him he would fight, but then who wouldn’t? He was a kindhearted man and I am sure he never killed anybody."

Bonzieb was particularly distraught by the news. He mustered the full force of his English-speaking abilities to declare, "Ameer Ben Ali no kill someone. He was bon homme, very good. He drink trop sometimes, but never want fight. Ben Ali not kill a woman, jamais, jamais, jamais."

They were all fiercely adamant about Ben Ali’s innocence and offered to testify to his good character. Jenalli even followed the reporter onto the street, declaring, "If Ameer Ben Ali kill woman the big American President Father can take me and cut my throat."

Sunday, May 10: Dr. Weismann's Infamous Mouse Experiment

On Sunday, a man only referred to as a "well known criminal lawyer" reached out to the New York Herald. Speaking under the condition of anonymity, the lawyer wanted to talk with the newspaper about something that had been eating at him ever since the news of Ameer Ben Ali’s arrest had been printed.

Ben Ali had been originally identified as "Frenchy," a violent and deviant predator who stalked prostitutes along the East River waterfront. But, the lawyer pointed, "Frenchy" was a very common nickname in New York City in 1891. Most of the city’s "Frenchys" were of North African or Middle Eastern descent. So, the lawyer concluded, this could be a case of mistaken identity; the police could have accidentally arrested Ben Ali in connection with the crime when they had meant to arrest a different, dark-complexioned man called "Frenchy."

Mistaken or confused identities among immigrants were fairly common in Gilded Age New York City. In the late-nineteenth-century, rapidly globalizing markets forced hundreds of thousands of European peasants to migrate to the United States in pursuit of better job opportunities. Most of these immigrants came from southern and eastern Europe; waves of Italians, Hungarians, Poles, and Russians had been flooding into Manhattan neighborhoods like “The Bend” since the mid-1870s. Not all the newcomers came from Europe, however. Thousands of Chinese immigrants had also begun to call New York home, while many black Americans moved to northern industrial centers, especially Manhattan, as they fled the violent and oppressive Jim Crow laws of the southern United States.

A colorized photograph of the Lower East Side, the vibrant intersection of New York's immigrant populations

These immigrants were met with racialized animosity in New York. Anti-Catholic, anti-Semitic, anti-Chinese, and anti-black sentiments polluted the air and poisoned the city’s wells. Nearly all of these second-wave immigrants—including the southern and eastern European ones—were considered non-white, and Anglo-Saxon New Yorkers feared this new presence could degrade American society.

Dr. Weismann

The basis for this fear was supposedly "scientific." Before 1889, the prevailing theory among the nation’s leading biological scientists was that the different races of humans were, in fact, different species that had evolved separately from one another. For many years, the belief among the nation’s scientific community was that Anglo-Saxon Americans could cultivate "American" habits in immigrants that would then become inheritable traits.

However, this belief was shattered in 1889 when a German scientist named August Weismann demonstrated learned traits were not inheritable by showing mice whose tails had been cut off did not, in fact, then give birth to short-tailed mice.

This set off a panic among the American scientific community. Weismann’s experiment proved that non-white immigrants could not be “improved” with Anglo-Saxon guidance. This refueled waves of racial hatred and distrust across the United States, and many of the nation’s leading scientists in the early 1890s warned that immigrants could corrupt and degrade Anglo-Saxon Americans.

As a dark-skinned immigrant, Ben Ali was subjected to both anti-black and anti-immigrant discrimination. Although Gilded Age New Yorkers were divided as to whether or not Ben Ali had murdered Carrie Brown, they were united in assuming Ben Ali was prone to savage behavior and deviant sexual desires because he was black. It didn't matter that Ben Ali was from a Berber tribe in North Africa, Manhattanites saw him as black. The inhabitants of the East River waterfront called him "black Frenchy" and a "black scoundrel." Even the newspapers referred to Ben Ali as "repulsive looking," "a regular cur," and "half stupid, half animal," among other racial epithets.

Systemic racism had socialized Americans to mention Ben Ali's supposed-savagery and race in the same breadth. To most white Gilded Age New Yorkers, common prejudices told them that Ben Ali, as a dark-skinned immigrant, was easily capable of committing such a violent and brutal crime like the murder of Carrie Brown.

Monday, May 11: Whispers at the Coroner's Office

On Monday, at long last, the cold spell broke. Although New Yorkers were still robbed of the pleasure of a spring sun, the cloudy skies did not stop temperatures from almost reaching ninety degrees in the mid-afternoon.

Monday also brought Ameer Ben Ali some company. In the afternoon, Jenalli made his way to 25 Chambers Street, the office of Levy, House, and Friend. Mr. Levy then took the little old man to see his friend Ben Ali in the Tombs. Ben Ali

was elated to hear of Jenalli's visit and practically bounded into the counsel room. Jenalli was also very happy to see Ben Ali, and the two greeted each other by bowing, then placing their left hands over their hearts, touching their nose with their forefingers, and bowing again. Ben Ali and Jenalli spent the next hour happily chatting together—sometimes even laughing—and when the visitation time was up, Ben Ali earnestly thanked Mr. Levy for bringing his friend to him.

In the evening, the Herald reporter who had originally located Jenalli escorted him back to his apartment in Brooklyn. On the ferry, Jenalli helped fill in more of his friend's story. The old man explained, in broken English, that Ameer Ben Ali was thirty-five years old and had a wife named Tiamena, as well as a son named Mohomet and a daughter named Fiara, all of whom lived in Algiers. Jenalli also explained that Ben Ali not only didn’t kill Carrie Brown, he had no idea who did, but had been cheerful in their meeting because he trusted that the authorities would soon recognize his innocence.

The corner of Centre and Chambers Streets; the office of Levy, House, and Friend was inside the building in the foreground on the right (which is now the site of the city's Surrogates Court building)

Although Ben Ali was in a good mood on Monday, Frederick House was, per usual, furious. At a quarter past two in the afternoon he and Emanuel Friend had gone to the coroner’s office for the Coroner’s inquest—a judicial proceeding to determine the cause of death of Carrie Brown and the first step toward a trial. They were expecting to appear alongside District Attorney De Lancey Nicoll, a jury, and whatever witnesses Nicoll procured. Coroner Louis W. Schultze was to preside over the entire procedure. However, when Ben Ali’s lawyers pushed open the door to the coroner's office, they were surprised to find only Schultze and Nicoll’s secretary, H.W. Unger, waiting for them.

Unger informed House and Friend that the District Attorney was seeking to postpone the Coroner’s inquest. Nicoll needed more time to put together a case that not only identified the cause of death as murder (a fairly obvious conclusion), but that showed Ben Ali was the murderer.

This infuriated House, whose steel-rimmed spectacles shook with anger as he angrily explained to Coroner Schultze that this delay was illegal. They could not postpone the inquest, House snarled, without a jury, witnesses, or a stenographer present. Moreover, House continued, the postponement would directly hurt their case.

“The prosecution in this case have the treasury of this great city behind it,” he complained. “We are conducting the case at considerable expense to ourselves and we will never get back a dollar of it. This delay is not fair to us.”

Coroner Schultze

Schultze coldly ignored House's plea and scheduled the inquest for Wednesday. He had heard the rumors.

For the past week or so, it had been whispered in the hallways of Police Headquarters that deep-pocket opponents of Inspector Byrnes were helping fund the defense of Ben Ali so that Byrnes could be humiliated in court.

The identity of these potential donors was unknown. There were a lot of parties that wished ill on the Chief Inspector. The money could be coming from the city's socialists and communists who hated Byrnes because he was a tool of elite interests and a ruthless strike-breaker. The money could also be coming from Tammany Hall, since Byrnes was the lone obstacle in their way of having complete control over the Police Department. Even Scotland Yard, seeking to humble Byrnes, could have been the source of the rumored funds.

No one knew who may or may not be helping fund Ben Ali's defense, but the mere presence of these rumors were enough to sink House’s plea. He was going to have to play by the District Attorney's rules.

Tuesday, May 12: A Cast of Characters

On the eve of the inquest into the murder of Carrie Brown, a savvy New Yorker might have taken some time on that cool Tuesday morning to think back and consider all of the different characters that had thus far played a role in the case. If he or she made a list of these individuals, it would have looked something like this:

Ameer Ben Ali: the man charged with the murder of Carrie Brown; an Algerian immigrant who was alleged to be a vicious sexual predator by the prostitutes of the East River waterfront and defended as a kind and gentle soul by his friends.

Andrew Carnegie: the Scottish-born industrialist who built a new Music Hall to help New York's nouveau riche seize control of the city's social scene.

August Bohle: the young man who had been viciously murdered, dismembered, and shipped to Baltimore in a trunk by Edward Unger in 1887.

August Weismann: a German biologist who proved learned traits are not inheritable, and accidentally refueled anti-black and anti-immigrant sentiments in Gilded Age New York City.

Carrie Brown: the murder victim; an elderly prostitute who had once been a happy mother of three in Salem, Massachusetts and then was driven into financial desperation by her alcoholism.

Charles F. MacLean & James J. Martin: two Police Commissioners (and civilian bosses of Byrnes) that were both staunch Tammany Hall members.

David Gilloway & Edward Smith: two prisoners who had been locked up with Ben Ali in the Queens County Jail; they both swore that Ben Ali owned a knife that was nearly identical to the murder weapon.

De Lancey Nicoll: the District Attorney of New York City and the man in charge of the prosecution against Ameer Ben Ali.

Dublin Mary & Mrs. Harrington: two prostitutes who claimed Carrie Brown’s mysterious companion was a regular customer of theirs.

Edward Fitzgerald: the night watchman and bartender at the East River Hotel who assigned Ben Ali a room on the night of April 23 and discovered Carrie Brown’s body in the morning of April 24.

Edward Unger: the murderer of August Bohle who confessed after being subjected to Byrnes' "Third Degree" interrogations.

Fredericka Mandelbaum: the criminal empress who escaped while Byrnes and former District Attorney Peter Olney argued with each other in 1884.

Jack the Ripper: the uncaught London serial killer who was rumored to also be the killer of Carrie Brown.

Jacob Riis: the Danish muckraking journalist who dedicated his life to exposing injustices and was covering the Carrie Brown case for The Sun.

Jay Gould & Cornelius Vanderbilt Jr.: two wealthy industrialists who were close personal friends of Chief Inspector Byrnes.

Jenalli & Bozieb: Ben Ali’s friends from Brooklyn who swore to his good character and (mostly) gentle nature.

"La Arabia": the Moroccan immigrant who was arrested as a possible suspect in London for the Jack the Ripper murders and was also briefly detained in Jersey City for the murder of Carrie Brown, but was released without explanation.

Levy, House, and Friend: the attorneys assigned to defend Ben Ali.

Frederick House: the spectacled and passionate lead defense counsel.

Emanuel Friend: the assistant defense counsel.

Mr. Levy: the third defense counsel.

Louis W. Schultze: the city’s coroner who was assigned to oversee the inquest.

Mary Miniter: a prostitute and regular customer of the East River Hotel who opened the door and let in Carrie Brown and her mysterious companion around midnight on April 23.

Nellie English: a prostitute who had once consorted with Ben Ali and claimed it was his practice to wander the hallways of the East River Hotel late at night and rob other prostitutes.

New York Herald reporter: the enterprising and anonymous journalist who discovered Jenalli and Bozieb.

Peter Olney: the former District Attorney who hired Pinkerton private detectives to publicly humiliate Byrnes.

Randolph Martine: the former prosecutor-turned-judged before whom Ben Ali was arraigned.

Richard O'Connor: the Oak Street Station police captain who was the first policeman on the scene in the East River Hotel.

Samuel Shine: the main bartender for the East River Hotel.

Thomas Byrnes: the Chief Inspector of the New York City Police Department; an ambitious man, Byrnes had reorganized the entire police force in his own image and staked his reputation on his transformation of the police into a supposedly world class crime-fighting organization (although he allowed plenty of corruption and other forms of malfeasance to flourish).

William McLaughlin: an Inspector; Byrnes' right-hand man.

Sixth Avenue and Broadway

The newly-erected Statue of Liberty

Fifth Avenue mansions of elites like Carnegie, Gould, and Vanderbilt

Tenements along Elizabeth Street

The Plaza Hotel

The Manhattan skyline in 1891

Wednesday, May 13: The Inquest Begins

On a sunny spring Wednesday, Ameer Ben Ali was brought out from his cell in the Tombs, handcuffed to a police officer, and taken in a carriage uptown to Coroner Schultze’s office on the corner of Second Avenue and 8th Street. When the carriage rumbled to a stop in front of the building at half past ten in the morning, a crowd had gathered on the corner. Men, women, and children all jostled with one another to try and get a glimpse of New York’s own Jack the Ripper.